Cities of Fuel: Fuel Holding Tanks and Industrial Land Use in New Haven

Will James (2019)

This somewhat mysterious site on the East Bank of the Mill River lacks an official street address or a clear owner. Several private companies including oyster fisheries and boat chartering services currently operate on the site mostly using area near the water for their business purposes. The rest of the site is strewn with a mix of heavy machinery like steam shovels and conveyer belts, scrap metal, and other industrial refuse. Crushed oyster shells cover most of the ground.

The site’s current condition, strewn with industrial refuse.

The defining feature of the site is a massive concrete cylinder across Mill Street from the John S. Martinez K-8 school. It was built in 1913 alongside a now demolished storehouse for the New Haven Gas Light Company, the main provider of gas street lighting in the early 20th century, and domestic gas in the later decades. Today, the outer concrete shell is all that remains. A large hole has been cut into one side for access, and it is now used much like the rest of the site: for storing dormant equipment and supplies.

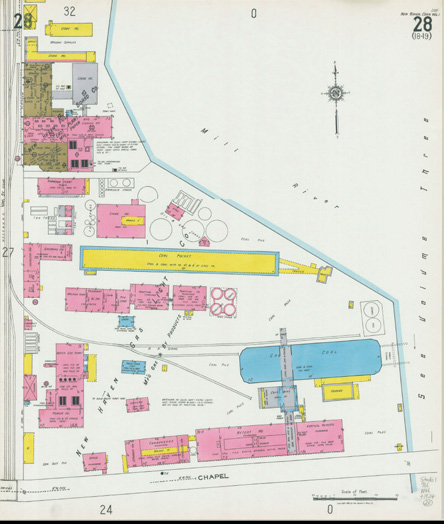

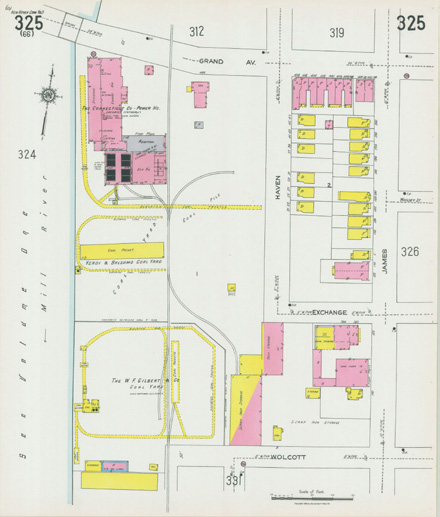

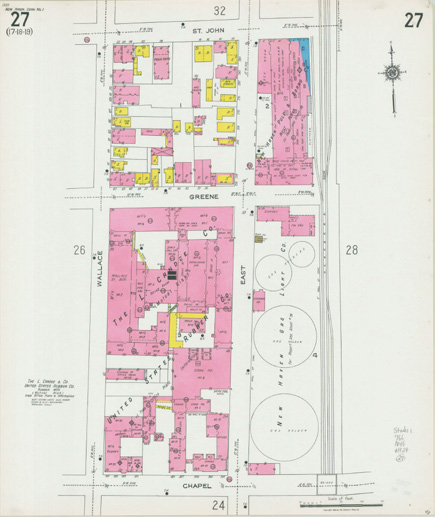

1924 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. maps showing numerous tanks, sheds, and piles for storing fuel in the neighborhood around the site.

The tank on the Mill Street site is a rare surviving example of what was once an extensive land use in industrial cities around the world. The late 19th century brought

the rise of affordable fossil fuels, but transportation costs were high. As a result, factories clustered near fixed path transit like harbors and railroad depots where they could recieve huge quatities of fuel (mostly coal) at minimal cost.

Neighborhoods like the one around the Mill River developed with residences, factories, and fuel storage all sharing the same close quarters. These places have largely disappeared. Center cities are often more valuable for other land uses, and fuel storage operation have increased in scale to the point that they need dedicated single-use campuses.

Neighborhoods like the one around the Mill River developed with residences, factories, and fuel storage all sharing the same close quarters. These places have largely disappeared. Center cities are often more valuable for other land uses, and fuel storage operation have increased in scale to the point that they need dedicated single-use campuses.

Left: Prominent fuel storage sites now lost to time, both in New York. Right: Gas holders repurposed and reintegrated into the 21st Century city. London and Vienna.

Past industrial land uses were sometimes unclean or unhealthy, but often lent an important sense of identity to the neighborhoods they occupied. For this reason, many are targeted for clean up and repurposing as civic assets - to preserve collective memory and meet the new spatial needs of an area. The tank at Mill Street and Saltonstall avenue presents such an opportunity for the Fair Haven neighborhood today.

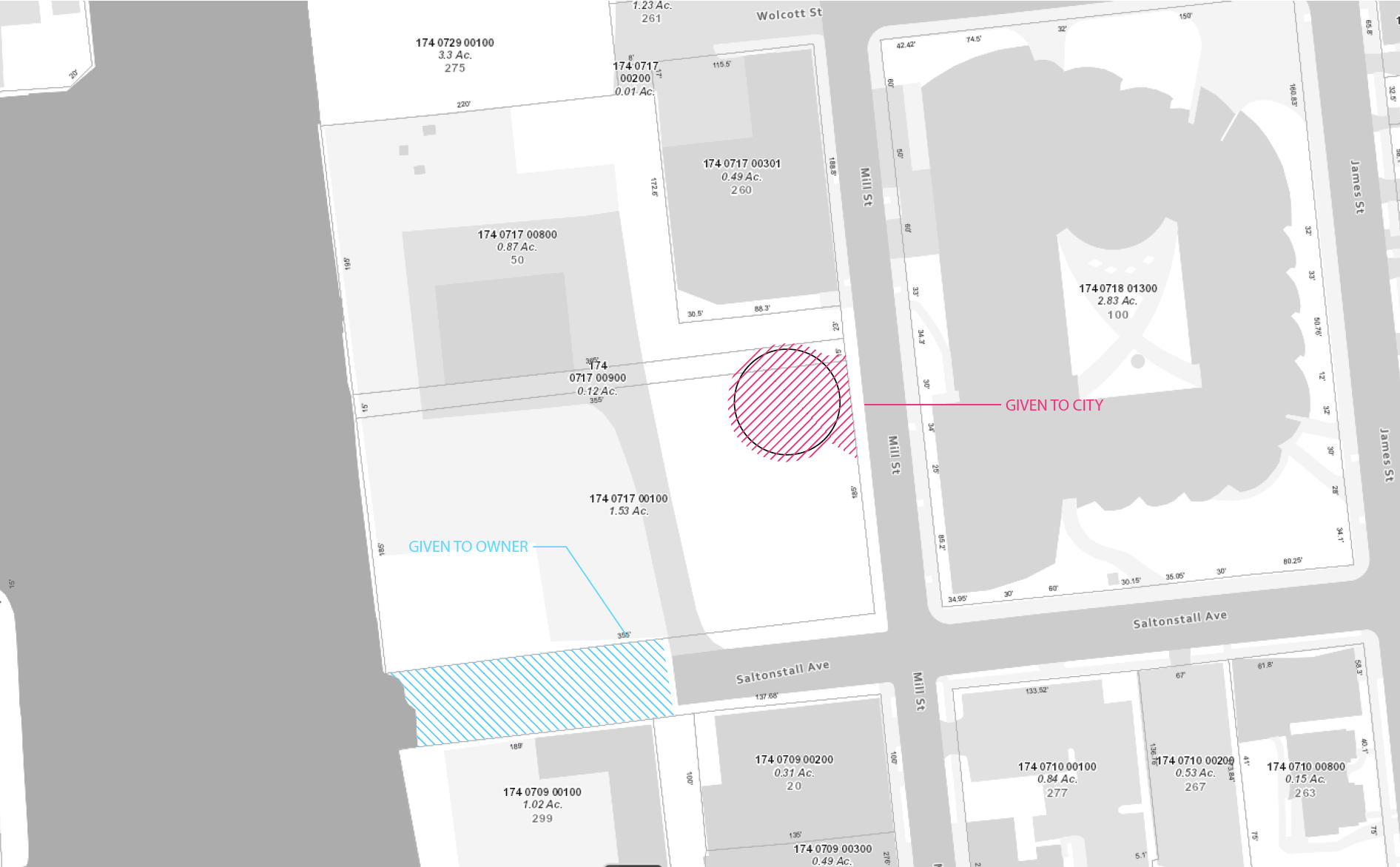

One complicating factor is that the tank is on private property, which is still used for small-scale commercial/ industrial purposes. It would be a contradiction of goals to appropriate land from active business to honor the memory of an industrial past - the past is still there! The project instead proposes a land swap. In exchange for giving the tank to the city as a new public space and landmark, the current owner would recieve Saltonstall Avenue’s current right of way to the Mill River. This includes 60’ of new river frontage, and a more accessable storage and staging area than the tank currently provides.

The proposal calls for clearing out the tank’s current contents and cleaning up the thicket of plants currently surrounding it. A new wall of board-marked concrete wraps one side of the cylinder, rising from grade to the eventual 40’ height of the tank at the entry. Between these two walls is a 8’ wide processional path, along which educational and interpretive materials about the site are sequenced. On the inside of the tank, the intervention is minimal. A surface of decomposed granite softens the space and provides a subtle color contrast to the gray concrete. The abstract form an powerful materiality of this space will be a draw for a variety of activities. Additionally, physical markers can be installed at other sites in the city relating to the history of urban fuel storage. Each one lists geographic coordinates, the structure’s material, storage capacity, substance contained, date demolished or decommisioned, and a small scale map. Together, they help create interest and intrigue in these relics of the industrial city.

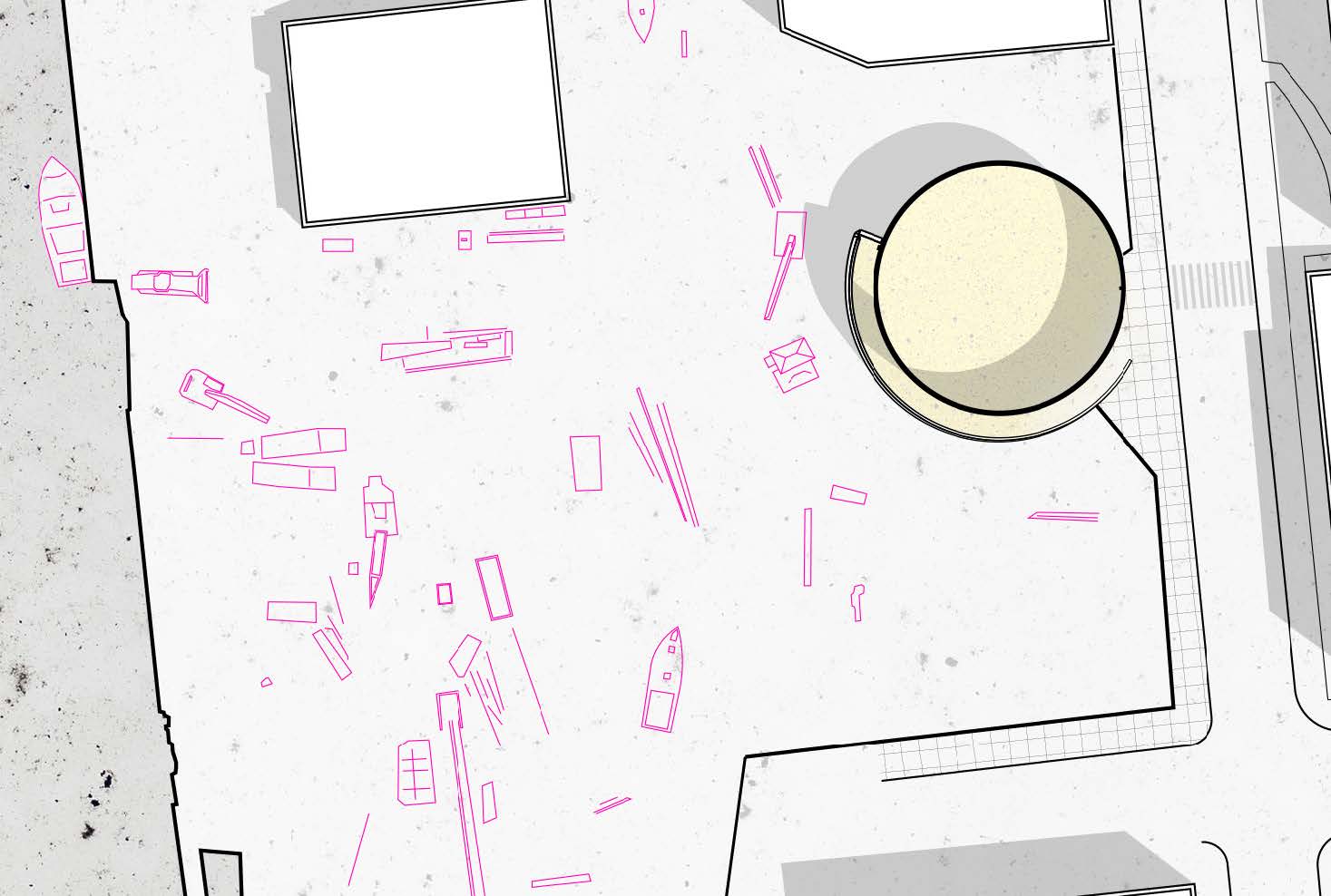

Project plan indicating new access to the tank, alongside disused equipment from the marine services company.

This project repurposes the tank as a new public space, and a new point of interest to connect the Mill River Trail to Criscuolo Park. Visitors enter via a curving passage between the old concrete wall and a new one, along which interpretive and educational material is inscribed. Inside, the abstract, monumental space is surfaced in a pale yellow decompsed granite, and provides a dramatic stage for live music, art exhibits, or any other small public function.