Not Ready to “Re-tire”: Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building and the Next Phase for an Icon

Larkin McCann (2019)

An original rendering of the Armstrong Rubber building from the office of Marcel Breuer.

Founded in New Jersey in 1912, the Armstrong Rubber Company quickly became one of the nation’s leaders in the tire industry, eventually moving to West Haven in 1922. By the middle of the twentieth century, Armstrong had continued to boom because of the company’s commitment to research and development of new technologies designed to make tires safer and more comfortable for the American driver. In 1970, Armstrong moved into its new headquarters, located here, in a $7 million building designed by world-renowned modernist architect Marcel Breuer. The building, originally consisting of both a tower and a sprawling, two-story wing expanding to the northwest, housed both executive offices and a major research and development department. In 1988, Armstrong was acquired by the Italian tire company Pirelli, which continued to own the building until the 1990s.

Advertisements from the Armstrong Company.

Marcel Breuer, born in Hungary in 1902, was one of the most prominent architects of the twentieth century. Breuer was educated at the Bauhaus in Germany, where he eventually joined the faculty. After fleeing Nazi Germany in 1936, Breuer came to the United States in 1937 to teach at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He formed an architectural practice in New York. Notable designs by Breuer included the 1966 Whitney Museum of American Art (now The Met Breuer) in New York, and the 1970 Becton Laboratory Building for Yale University on Prospect Street in New Haven. He was also well known for his furniture designs, like the Wassily Chair with bent tubular steel. Like many of his other buildings, the Armstrong building is composed of intricately designed prefabricated concrete panels. Ever the concrete connoisseur, Breuer created some of the building’s most exquisite details in the design of the stairwells.

Left to Right: Portrait of Breuer; Armstrong facade panel drawing; Armstrong stairwell; Breuer’s Whitney Museum.

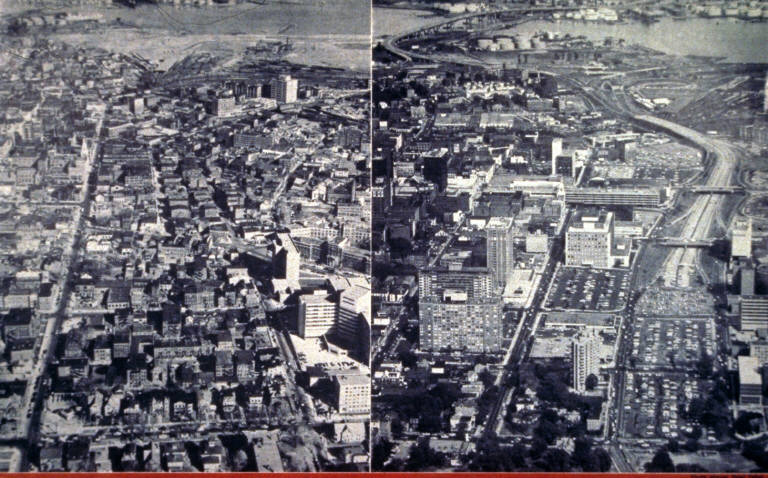

With the advent of the Interstate Highway system in the 1950s and 1960s, it became increasingly important for cities like New Haven to connect themselves to the emerging network of new roads. In New Haven, Mayor Richard C. Lee answered this call by carrying out large-scale demolition in neighborhoods that he argued were blighted slums. The Oak Street Connector was intended to draw people into the city from the I-95 and I-91 interchange. The Armstrong Building is uniquely positioned at the crux of this massive intersection of highways, and to this day effectively serves as the iconic gateway to the city for northbound traffic on Interstate 95. The neighborhoods leveled in the name of the automobile will never be seen again; but their legacy has remained thanks in part to a recent student project that posted signs around the Oak Street Connector with quotes from those who remember the neighborhoods.

Before and after photographs showing the construction of the Oak Street Connector through the middle of New Haven.

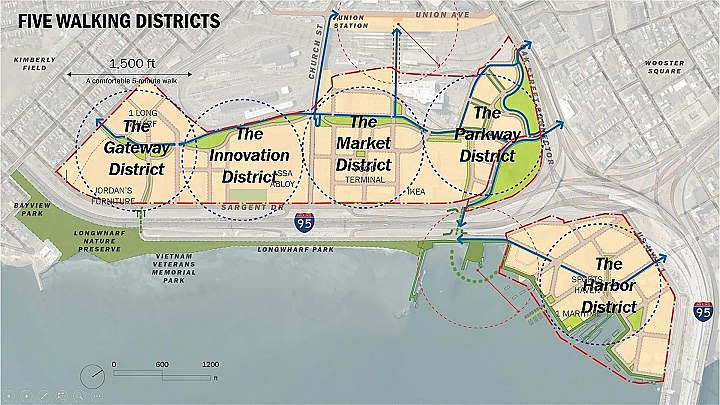

You are standing on land fill created when the largest wharf in America was infilled to construct Interstate Highways 91 and 95. With the addition of many acres of reclaimed land along the city’s new waterfront, New Haven planned a major industrial district here, of which the Armstrong Building was one of the first major components, along with a large building for Sargent, and another for the New Haven Register. Because the land on Long Wharf was so easily connected to the highways, the Armstrong Rubber Company seized the opportunity to relocate its headquarters to its new building here. Now that much of the industrial fabric of the Long Wharf area has given way to retail stores like Ikea and Jordan’s Furniture, there has been a more recent push to redevelop Long Wharf as a more pedestrian-friendly area connected to the New Haven Harbor, opening up a new realm of possibilites for the Armstrong Building.

Ikea purchased this property and planned to demolish the Armstrong Building in 2003, but preservationists argued to save the tower portion of the building. Still, Ikea demolished the two-story research and development extension in order to make way for what is now this large parking lot. This sign is located at the spot where the northwest corner of the building originally stood. The original prefabricated concrete panels from one end of the two-story portion were preserved and relocated to the lower part of the tower, where they were simply bolted in place to enclose what was left of the building. In fact, as you walk up to either end of the building today, you can look through the windows to see the backs of the panels and their attachment. Since Ikea took over, the building

has remained vacant. The facade facing Interstate 95 often serves as a massive advertizing billboard for Ikea products.

Recent plans suggest a more walkable Long Wharf district with cultural opportunities.

Because Ikea has never had any specific use for the Armstrong building, it has remained vacant and unused since the 1990s. Ikea has often used the building for advertising, but more recently, has allowed for temporary art installations. In 2017 artist and New Haven native Tom Burr worked with the Bortolami Gallery of New York to create an art installation on the first floor of the building, which remined there throughout the 2017 calendar year. The interest of the art world in the building generated interest from the real estate development world. In 2018, the New Haven Register announced that Ikea was “in partnership with the city to promote possible uses,” including an adaptive reuse project that would turn Breuere’s concrete megalith into a hotel. The article concludes, “It’s ironic that New Haven’s urban renewal obsession that demolished hundreds of structures created the site for a building worthy of saving.”

Top: The original exterior of the Armstrong Building; The building’s present use as a billboard for IKEA.

Bottom: A recent temporary art show held inside.

Bottom: A recent temporary art show held inside.

The stories of this building and the development of this industrial area around it are unknown to most passers by and visitors to IKEA. By exhibiting this interpretive material in various locations around the parking lot, visitors can be drawn in by the disctictive architecture of the building, and in the process can learn about industrial history, urban renewal, cultural opportunites, and more. Each interpretive story is displayed in a mockup of Breuer’s precast facade panels, helping to orient these stories back to the architecture.