Armstrong Carriage Factory: Shifts in Industry and Adaptability

Ben Thompson and Louis Koushouris (2020)

This project was presented as a presentation. Slides are on the left and the transcript is on the right. Click on the slides to view as a full screen presentation.

We are Louis and Ben, our Project is called Armstrong Carriage Factory: Shifts in Industry and Adaptability.

Our site is the M Armstrong Carriage Factory located at 433 Chapel. We are proposing an interpretative strategy for this building which ties the carriage manufacturing industry in New Haven to the early Automobile industry in Detroit. This shift in methods of industry, from the Industrial Revolution to Fordism, has architectural implications evident in the M Armstrong Carriage Factory.

This is the factory in its current condition.

And this is it around 1890.

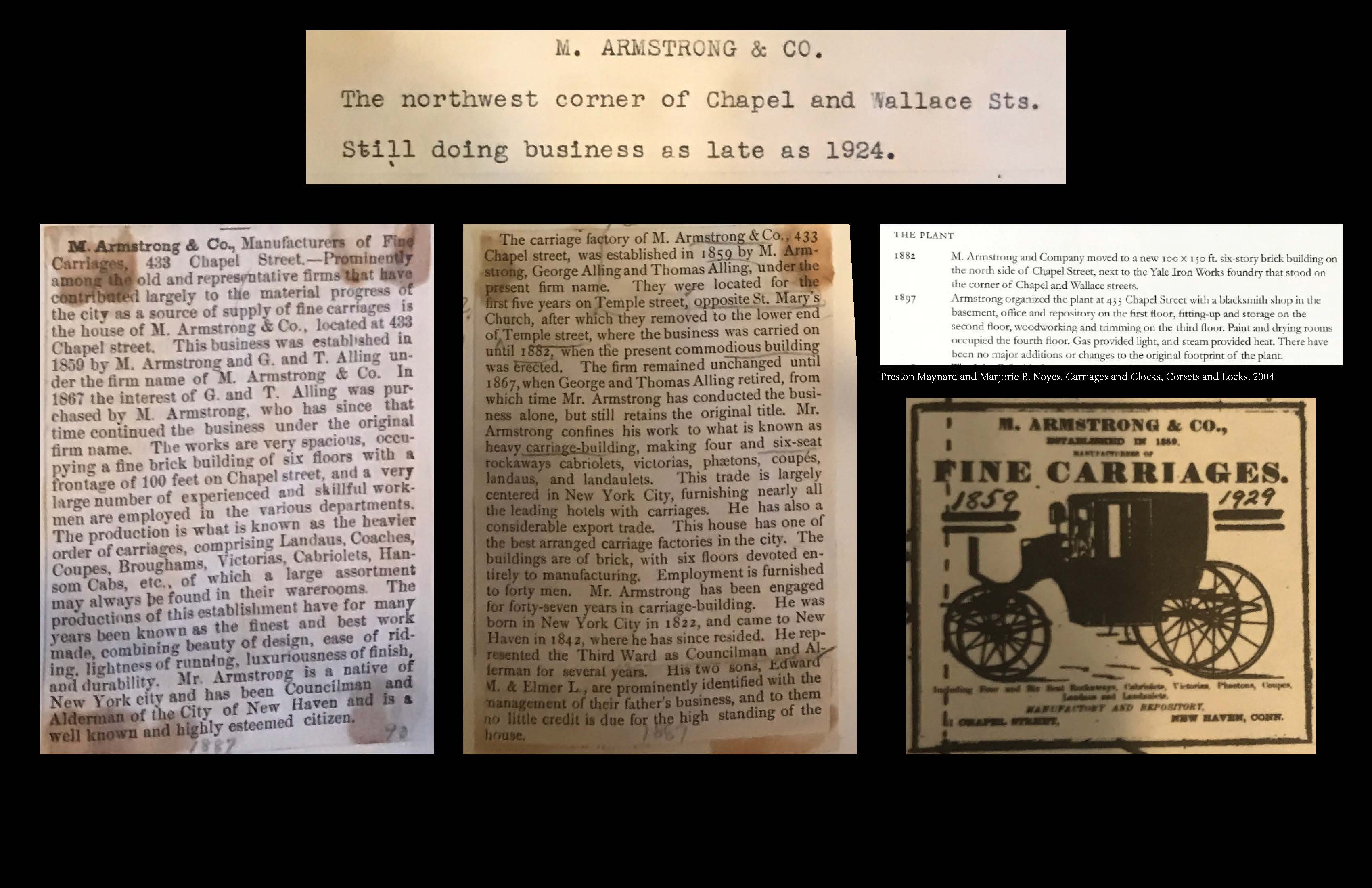

Built in 1882 the building remained a Carriage Factory until 1924/1929. Armstrong started manufacturing carriages in 1859 at a location on Temple Street. The new building on Chapel was built specifically for Carriage manufacturing. He came from NYC and was a New Haven Alder. They made heavy carriages, four and six seaters and sold them to hotels in New York City.

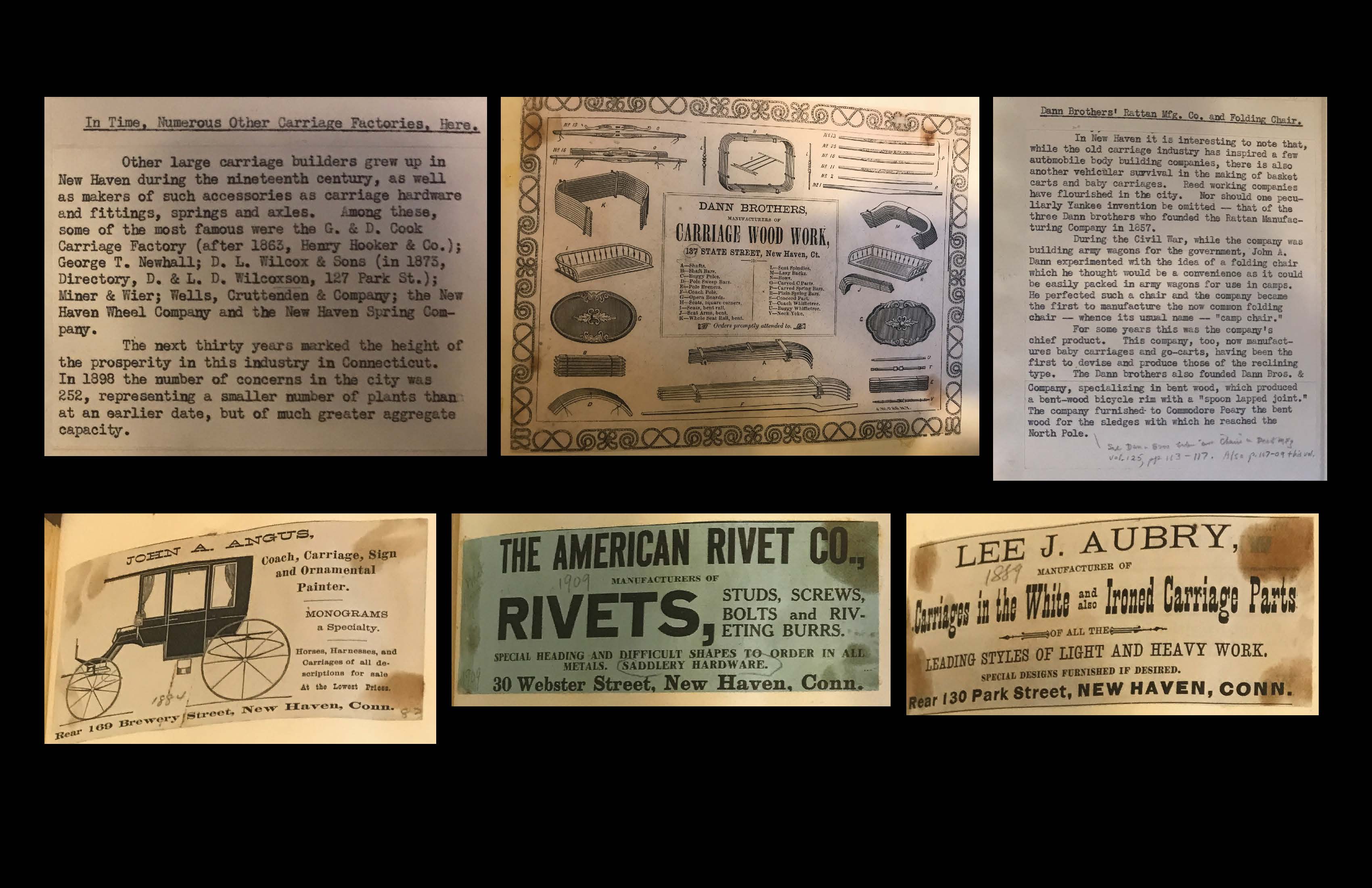

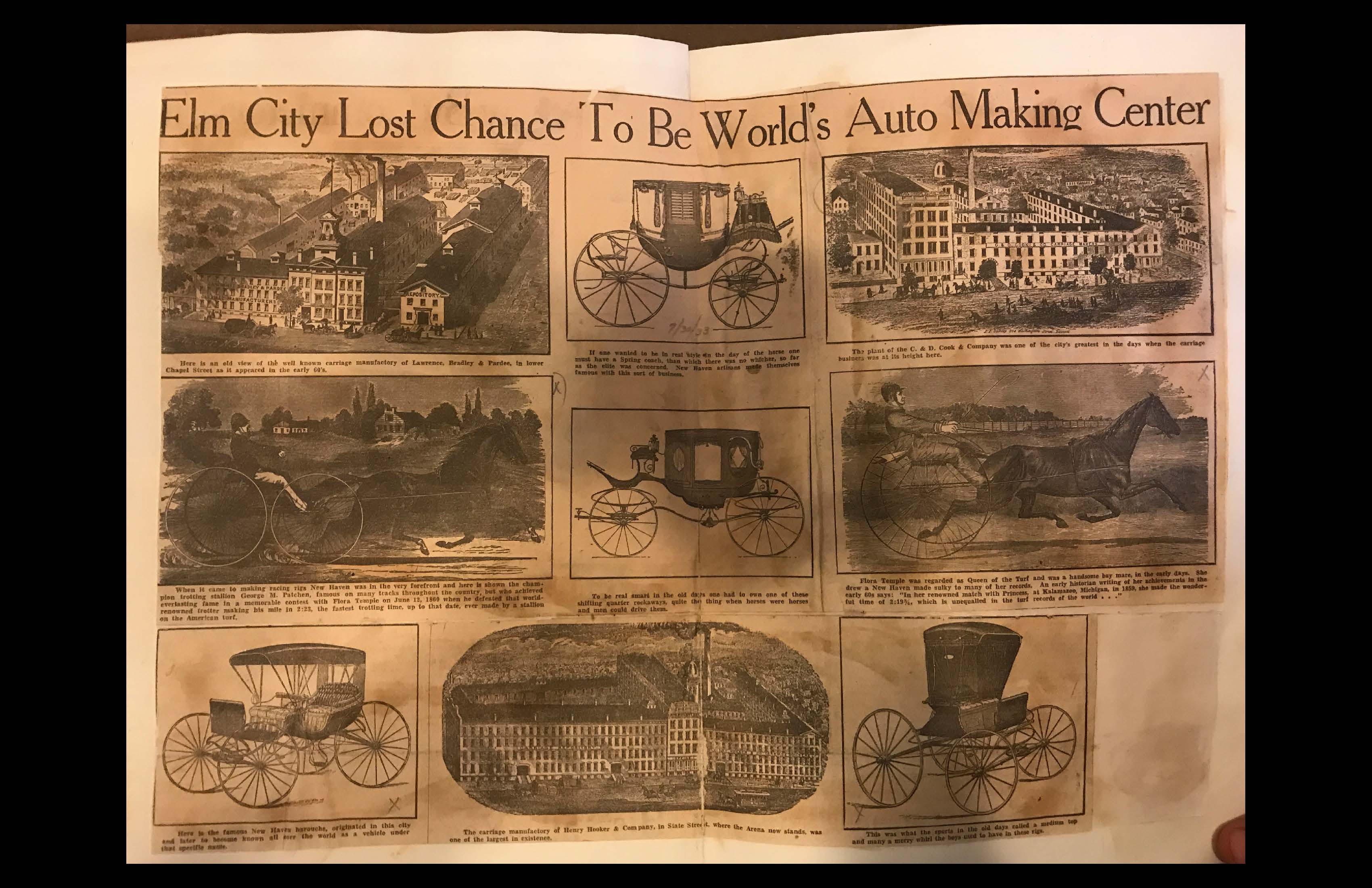

Part of a wider network of carriage manufacturers in New Haven. In 1898, over 250 enterprises in some aspect of carriage manufacturing. We also see specialized companies, this extended district sold rivets, provided painting and blacksmithing services. Earlier, New Haven could even have been called an arsenal of democracy, providing wagons for the Union in the American Civil War.

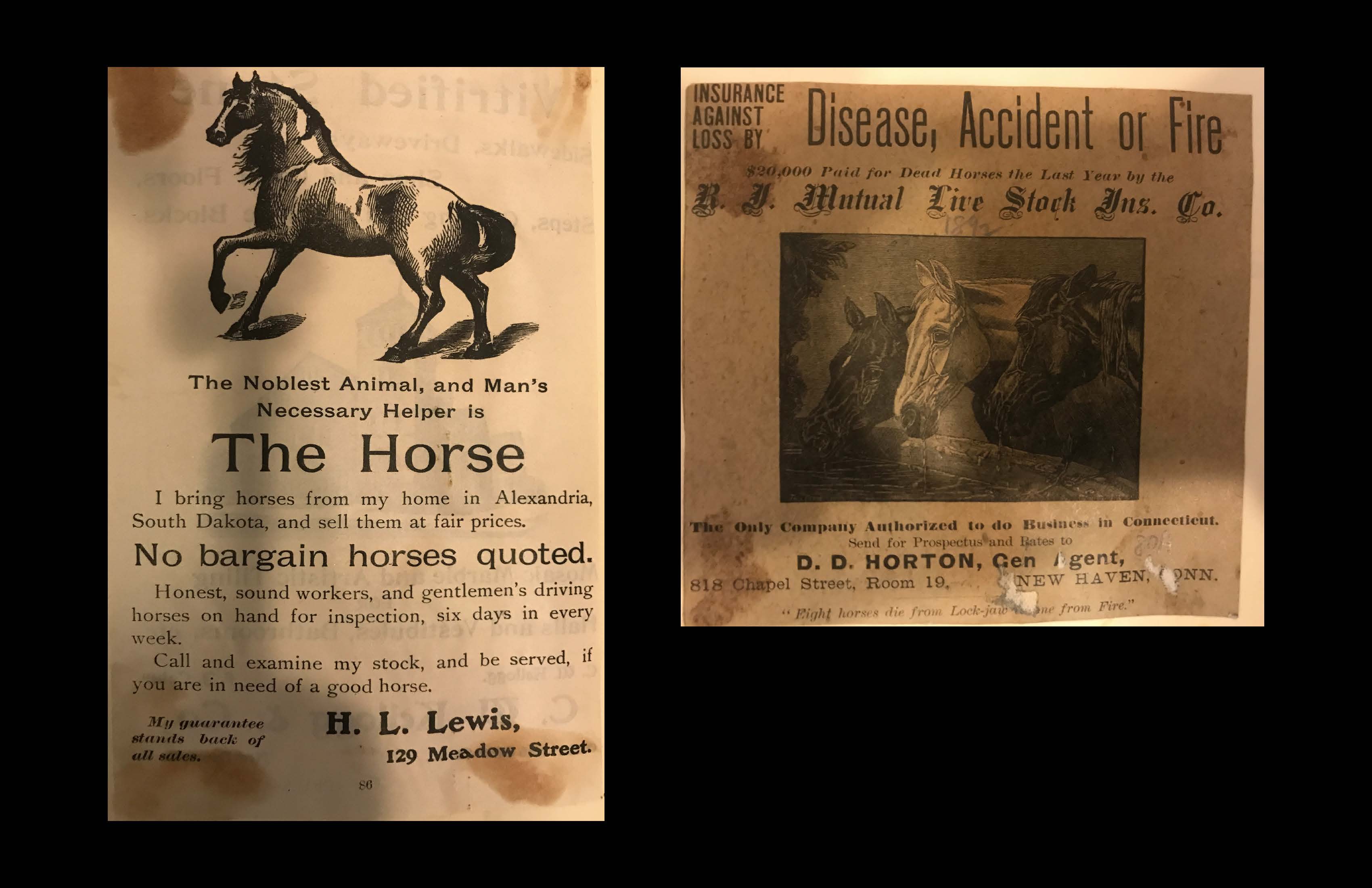

The horse and carriage were the main means of getting around. In 1890 there were 20 million horses in the US. There were even insurance plans for horse ownership, much like there would be for automobiles. Disease / accident / fire.

Two advertisements from the 1880’s boasting the significant variety of coaches made by M Armstrong; Landaus, Cabriolets…

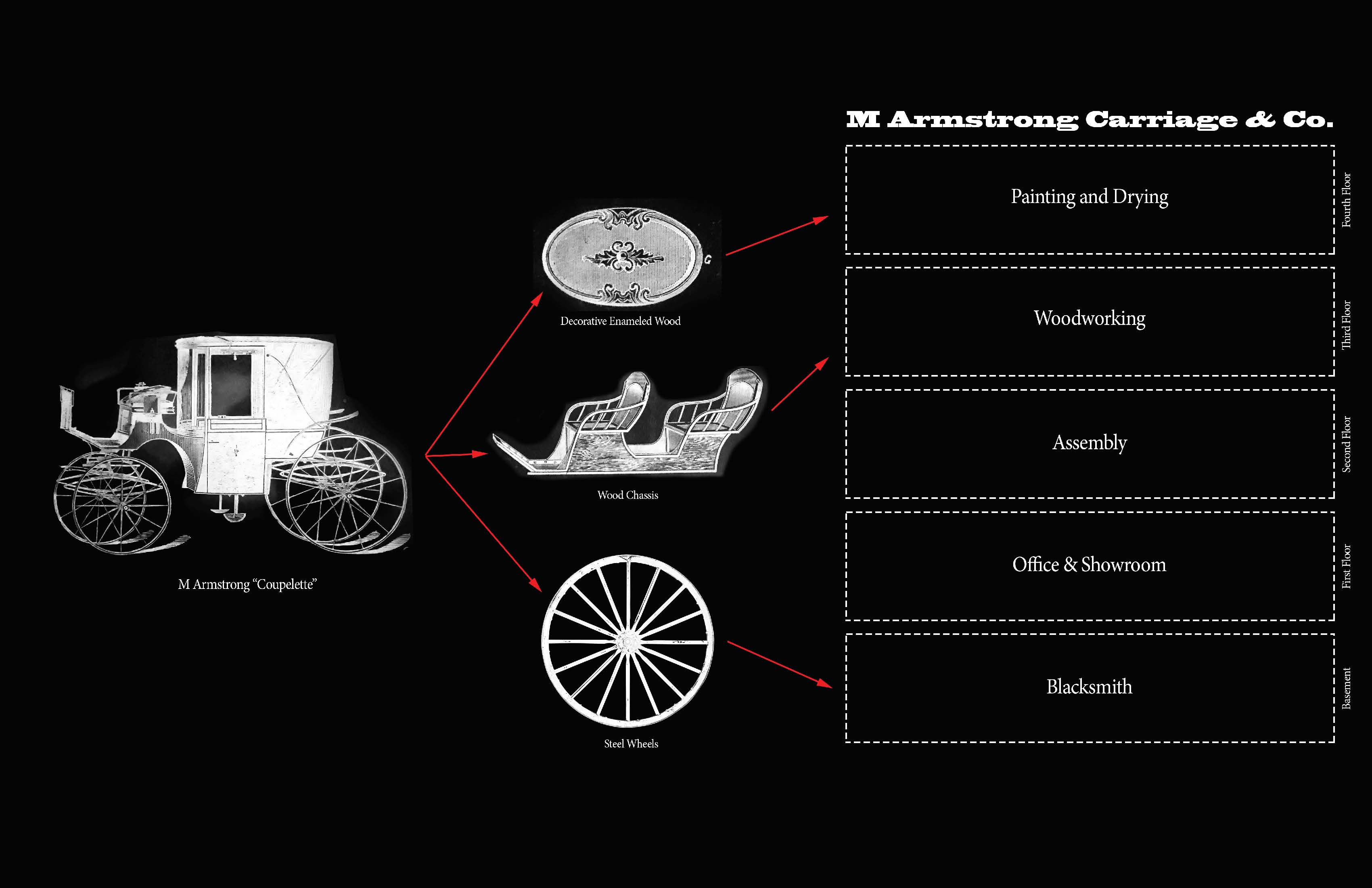

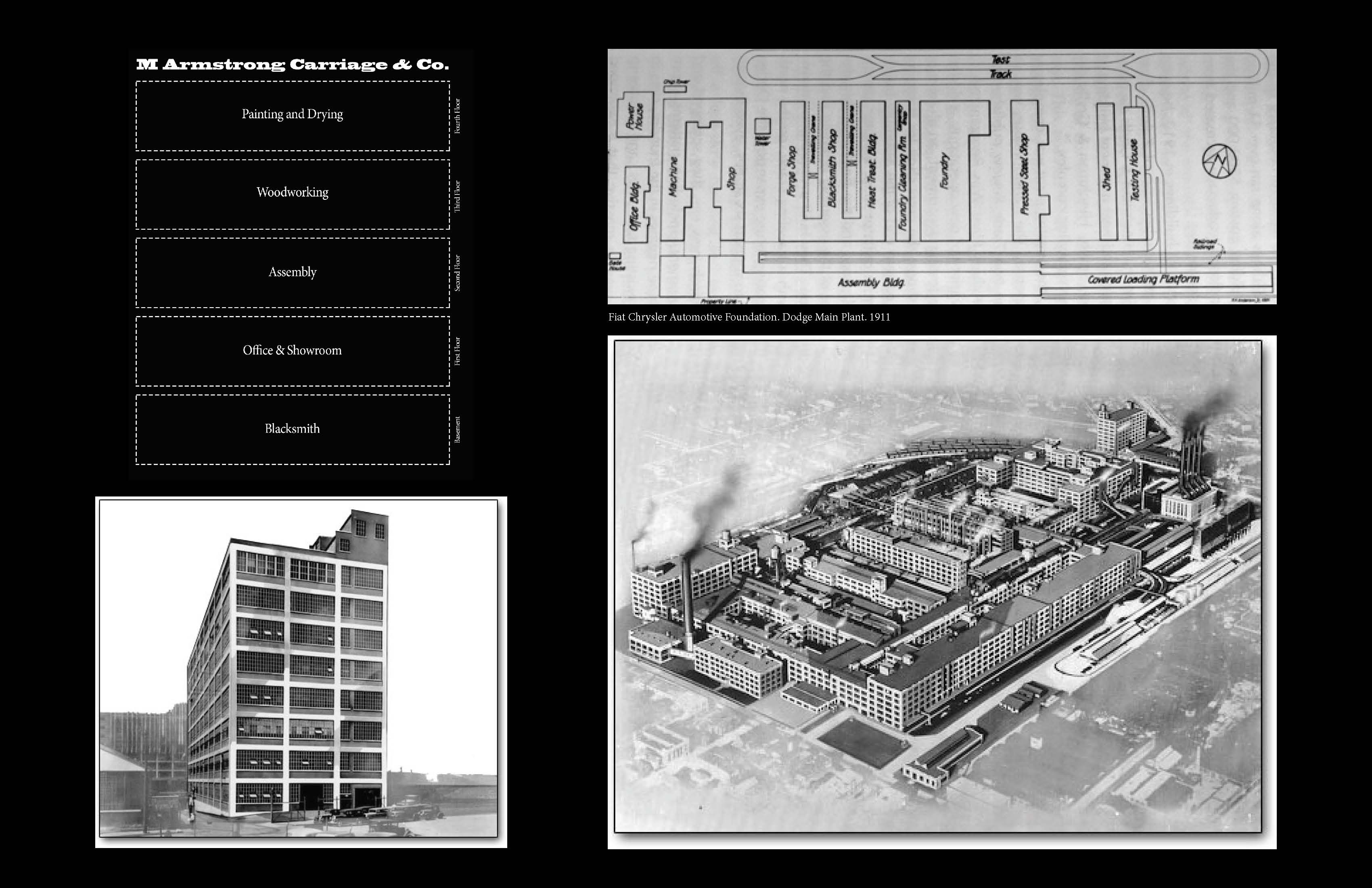

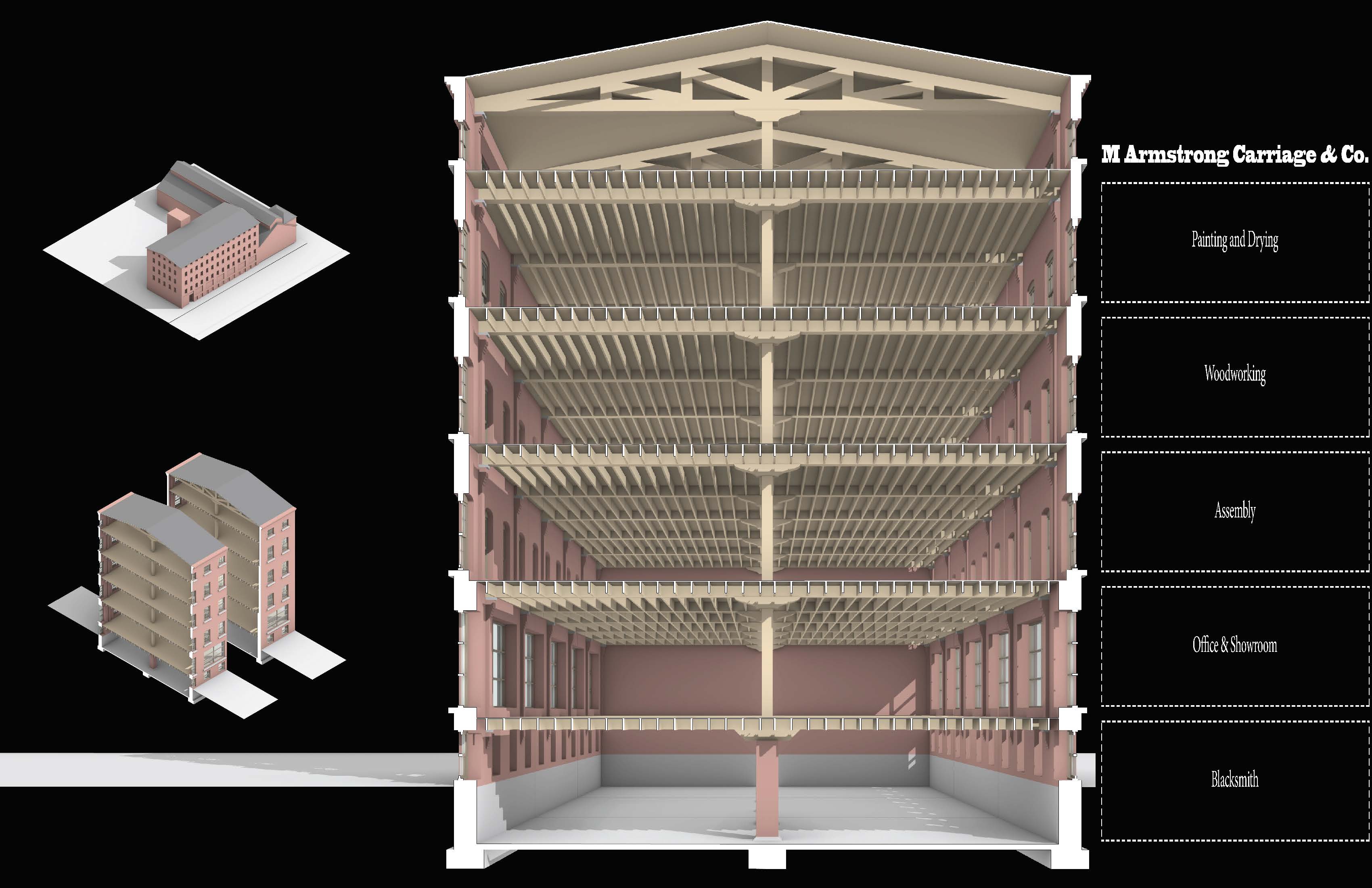

The building’s architecture was designed with the process of manufacturing the carriage in mind. The main elements of the carriage are the woodworking, painting/lacquering, and the metal work. The building was conceived to have the blacksmithing in the basement, the offices on the first floor, assembly on the second, woodworking on the third, and painting and drying on the fourth. The carriages were transported from floor to floor by means of a large dumbwaiter in the rear of the building. The typical construction of the time was load bearing masonry and timber, the shell of the building was made of brick to reduce the chances of fire.

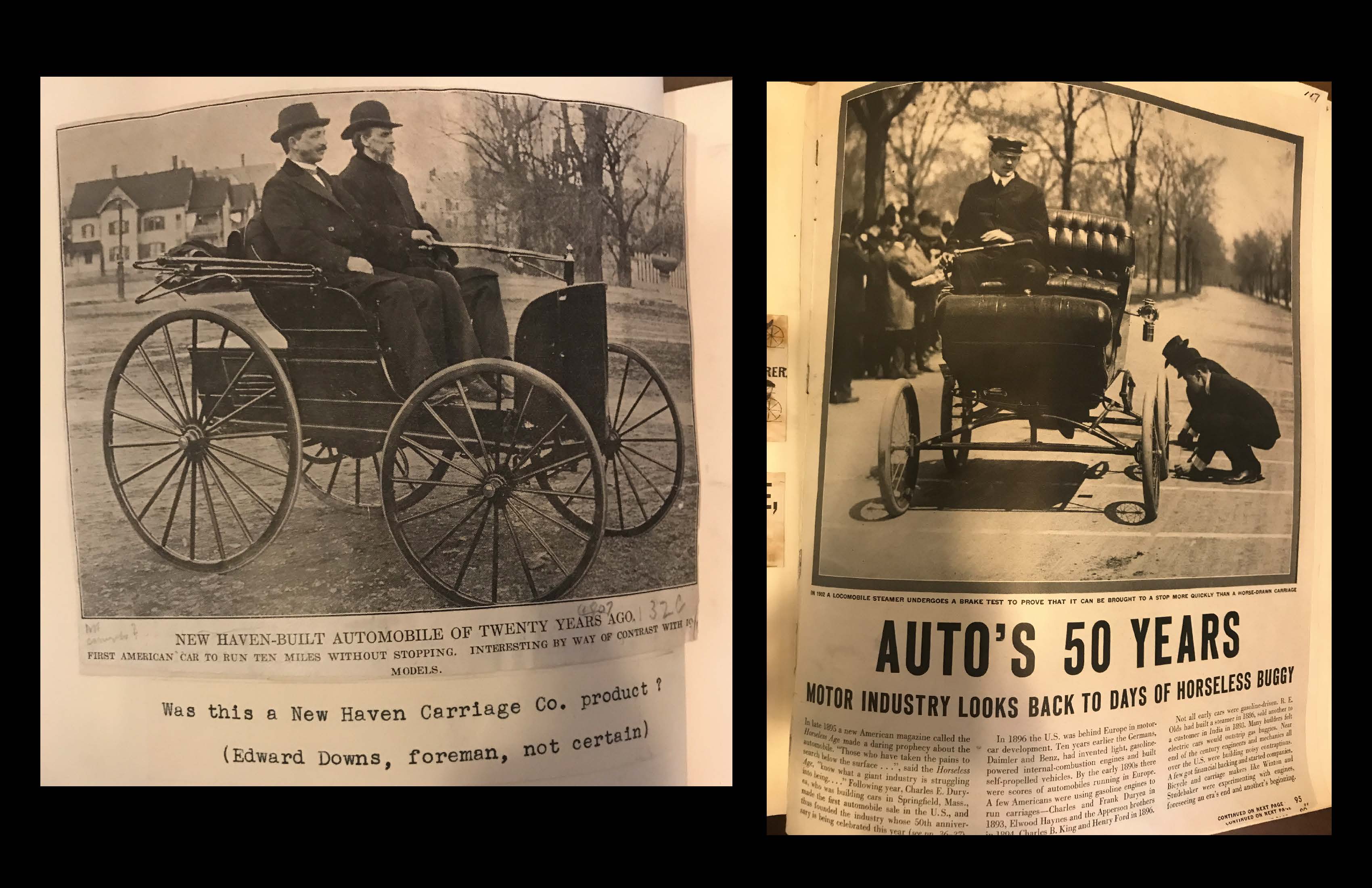

These carriages became the armatures for the first automobiles in the early 1900’s. These prototypes boasted different methods of combustion like steam, electric and finally gas powered. These are two examples of prototype Horseless carriages. First car to run ten miles without stopping.

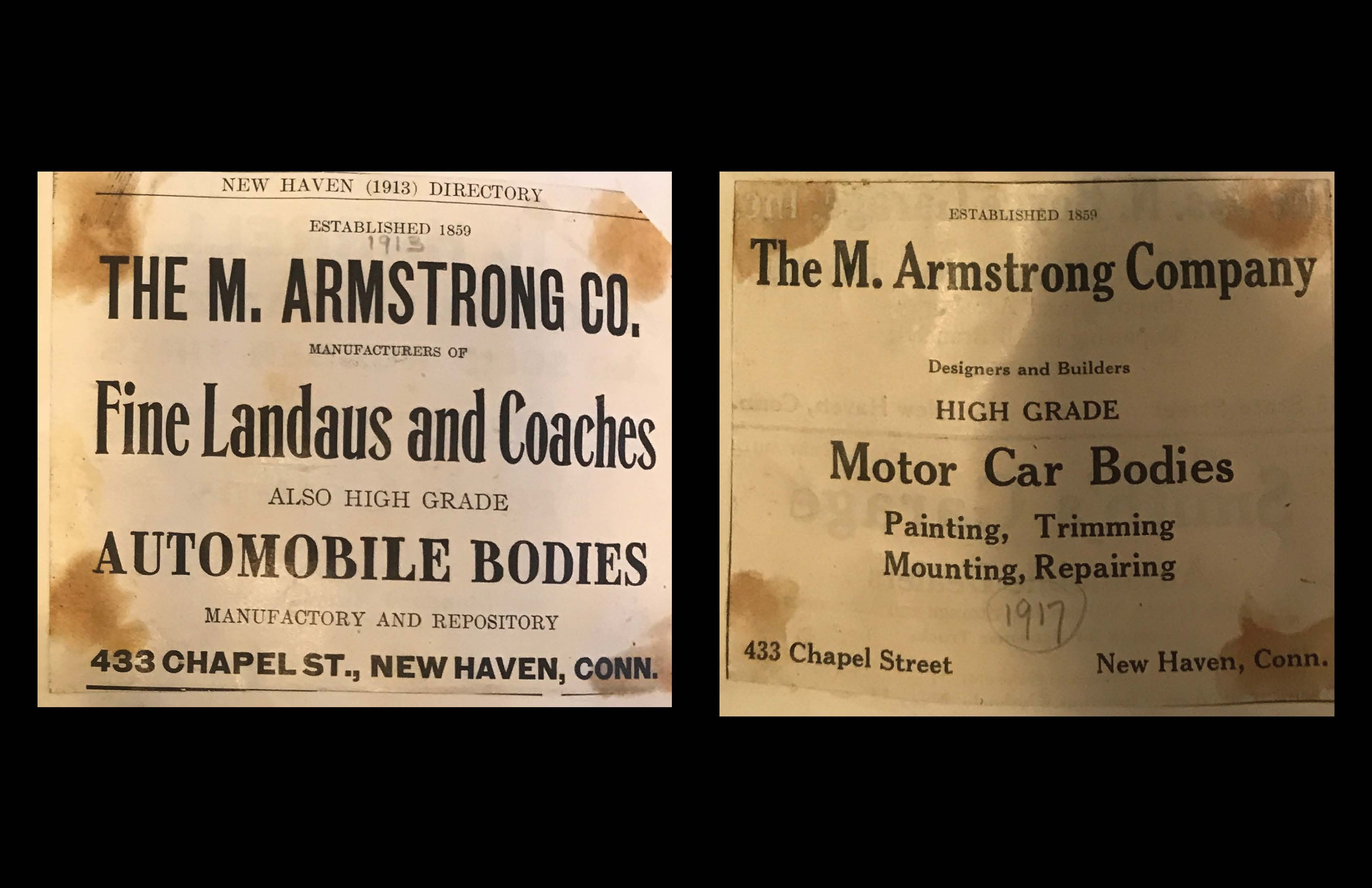

The horseless carriage began as a novelty but by nineteen-thirteen we see that the popularity has increased so much that the M Armstrong Carriage Factory had to convert to sell automobile bodies.

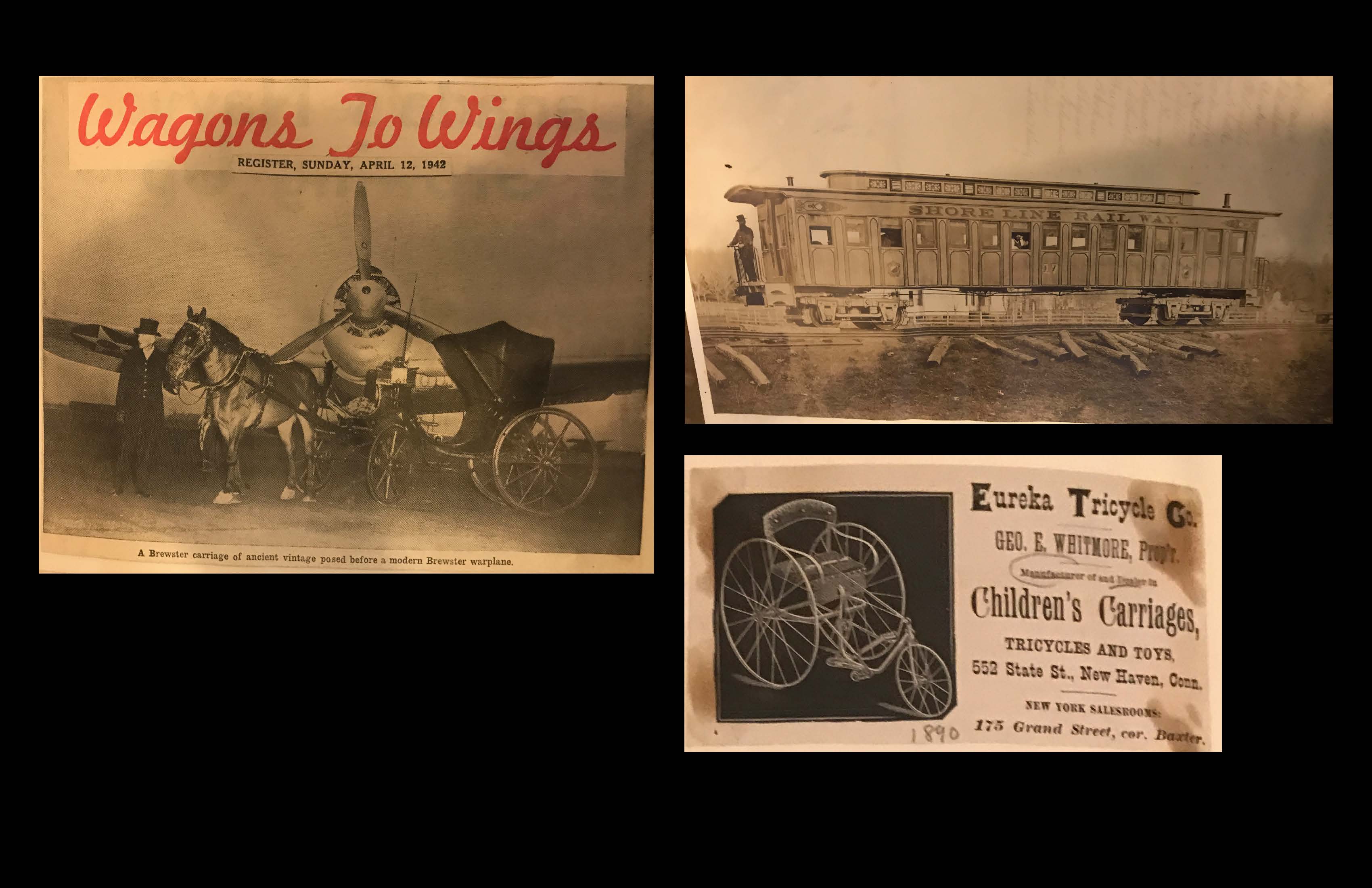

Around this time, other companies started jumping ship. Brewster Carriages became Brewster Aeronautics and moved to Long Island. Cook converted to railroad coaches. Other smaller companies converted to children’s toys, here an early tricycle.

Here we see the carriage in a lineage of something that resembles the modern car. Eventually the horseless carriage completely converted to the automobile. The industry moved from modifying carriages with engines to building bodies specifically as automobiles.

This is a watershed moment. While New Haven was the capitol of carriage manufacturing, the secret to automotive manufacturing was standardized parts and hyper-specific assembly lines. Henry Ford took the methods used by M Armstrong and the other carriages factories like Cook and Brewster and stretched them into what would become known as Fordism.

Detroit became the automotive capitol simply because Henry Ford happened to live in Detroit and the access to timber, iron ore, and the rail systems through Chicago all proved valuable factors to why his ventures succeeded. His success spawned competitors like the Dodge Brothers and General Motors who also set up shop in Detroit. In 1910, the enormous Dodge Main plant was built. We can see the similarities to M Armstrong. Rather than one building within a carriage factory district, the factory inhabits a campus with multiple discrete buildings housing the even further separation of processes. This time the buildings are reinforced concrete engineered to hold incredibly heavy loads and designed by Albert Kahn.

Eventually the process became more and more horizontal and monolithic. The Dodge Main plant was demolished in 1981. The vast size and hyper specific use of the building dictated its form and limited opportunities for conversion to other uses. The plant was replaced by new manufacturing facilities built on large tracts of land bought cheaply in the undeveloped farmland around Detroit. Warren Truck assembly is indicative of this shift, being built in Warren, a suburb of Detroit, and constructed as one long giant single-level mat building.

This is the campus compared to the district. Campus being related to Fordism, and district before that. Here we see the ghosted carriage network. These granular independent businesses made up a smaller connection within a neighborhood.

The product of the widespread dissemination of the automobile actually plays into why most of the buildings involved in carriage making were destroyed and also why this specific building still stands. This is a drawing of extruded Sanborn maps. The Armstrong Factory building dodged the formation of the highway, where the neighborhood to the East remains designated to be a manufacturing district.

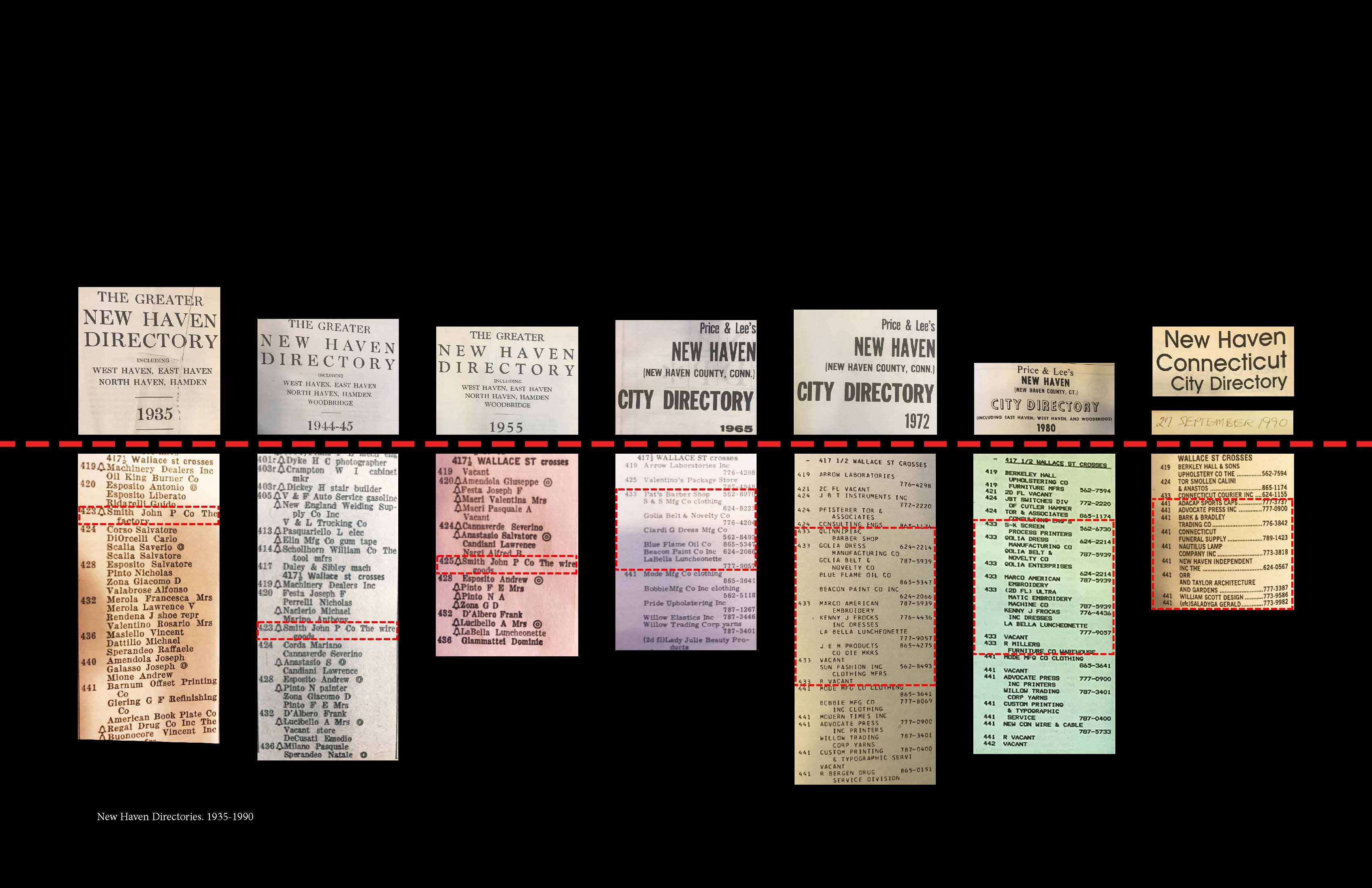

M Armstrong Factory Building Directory – This image is an index of tenants through the building’s lifespan. Of course originally constructed for the production of carriages, their fabrication process occupied the entire building. Next was JP Smith Wire Co, who manufactured wire baskets using techniques developed for carriage seat design; the business did not occupy the entire building. As large scale manufacturing vacates New Haven, the building is subdivided into multiple smaller tenants. Pats Barber Shop, S&S MFG Co. Clothing, Golia Belt & Novelty, Ciardi Dress, MFG, Blue Flame Oil, Beacon Paint Co., Labella Luncheonette, Marco America Embroidery, Kenny J Frocks Inc. Dresses, CT Courier.

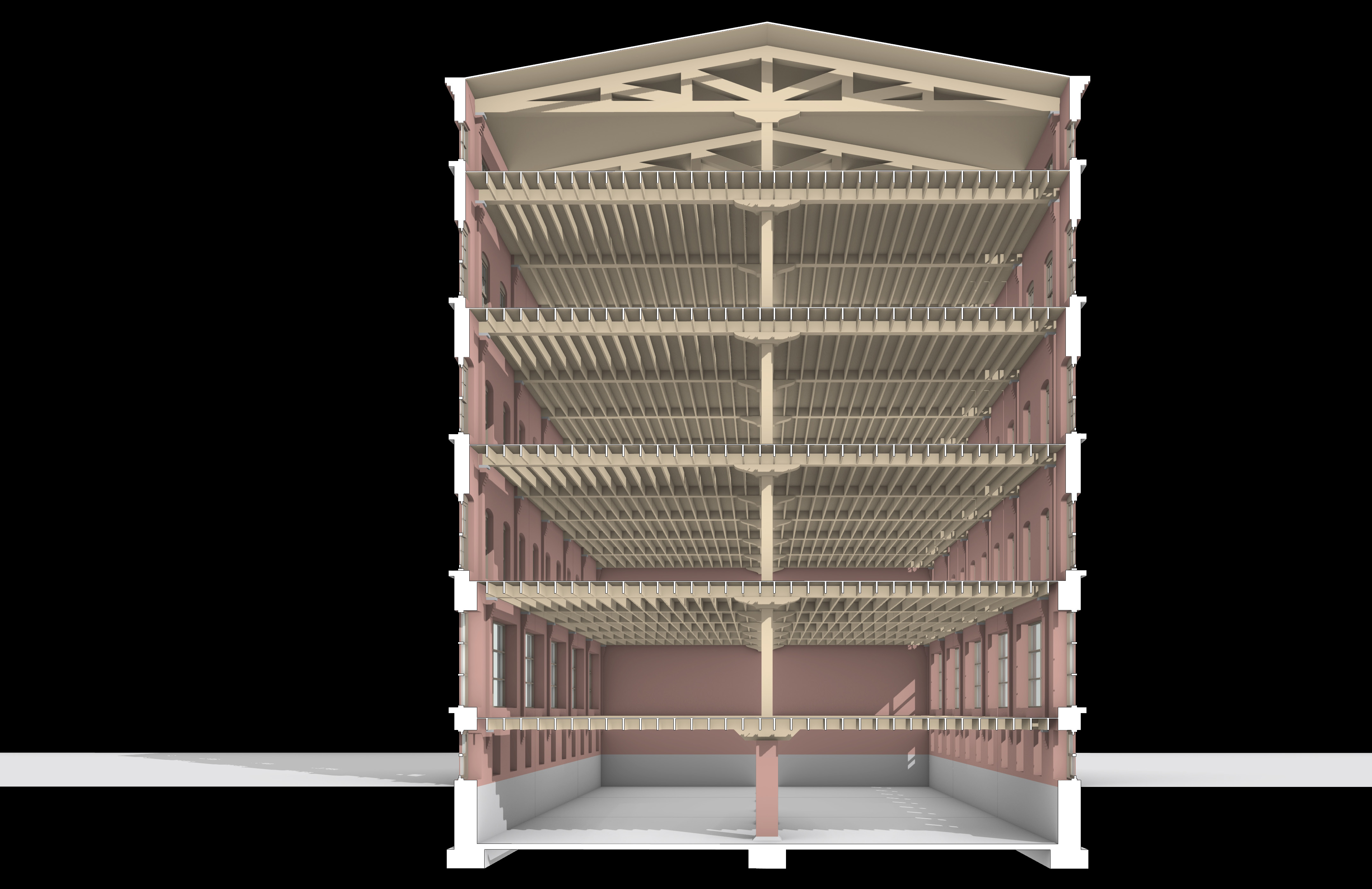

Section / Elevation – The building is load-bearing brick masonry and timber construction; it has a stone foundation. A wythe is a continuous vertical section of masonry wall one unit in thickness; the building tapers from a couple brick wythes at its top to several at the base because there is a greater structural load at the bottom. Large timber posts support beams which span between walls and bear on brick corbels. Older double hung and newer fixed windows fill the apertures.

Final drawing – The M Armstrong Factory Building is a manifestation of the industrial revolution before Fordism. It represents skilled labor and craftsmanship before the horizontal assembly line and standardized parts. Fordist methods dictated highly specific factories; they only served a single purpose. Conversely, the granularity of production in older factories, like M Armstrong, equates to an adaptability of use. The robust structure with open floors can be easily partitioned and subdivided for multiple occupants. We believe the building could be adapted to a variety of uses that support its context.

The building is currently slated for foreclosure. At the beginning of the class, this article was what drew our attention to the building in the first place. We think it is critical to engage public interest in the rich New Haven history of the ghosted carriage network, in order to have a greater understanding and appreciation for the factory and its ties to the memory of the neighborhood.